Preemptive Coercion: The Authoritarian Politics of Informal Settlement Governance in China

What explains authorities’ eviction of migrants and clearance of informal settlements? Social sciences have a long tradition of addressing this issue through the lens of development. As political scientists shift towards a power-centric perspective, the focus remains largely on politicians’ compromises with informal settlers under the pressure of winning elections. How power maintenance drives the governance of informal settlements in non-electoral contexts remains under-explored.

My book project introduces preemptive coercion to describe the political control rationale behind informal settlement demolition under authoritarianism. The inherent spontaneity and lack of standardization make informal settlements less legible for authorities to monitor and control. As a result, authorities are concerned about being unable to detect early and indirect threats to stability hidden in these communities, even though such threats have not escalated into widespread resistance. This fear can prompt authorities to employ coercive measures in advance, such as forced demolition, in the routinized governance of informal settlements.

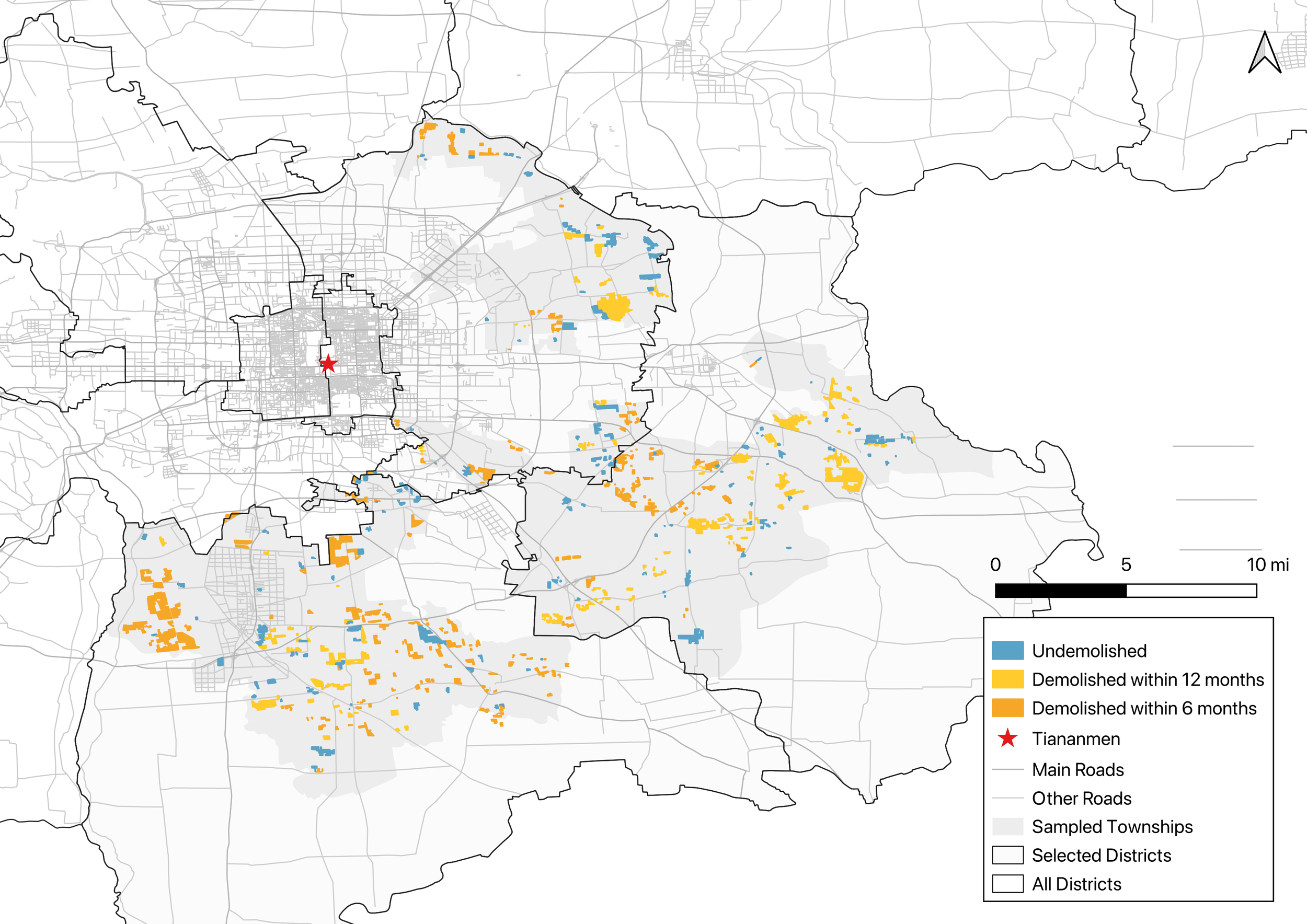

This project selects China as the regional focus, a case where the prevailing developmental theory struggles to explain the recent dynamics. I use a mix of qualitative and quantitative methods, including remote sensing data analyses, design-based inference, interviews, and ethnography.

In the first empirical chapter, I examine the presence of preemptive coercion for political control, based on a case study of Beijing’s demolition of informal settlements between 2017 and 2018. I empirically look into whether the government targeted informal settlements that were less legible for detecting signs of instability. I draw from innovative sources like satellite imagery and digital street views, compiling a unique dataset of 320 informal settlements. In the second chapter, I extend the lens of preemptive coercion to study the impact of COVID-19 surveillance. Combining case studies and a time-series dataset of 65 townships in Beijing from 2017 to 2023, I identify a causal relationship: townships with more COVID-19 cases increased their information collection of informal settlers, which led to the reduction of demolition rates. The third chapter delves into how urban space facilitates a wider sharing of grievances among ordinary citizens in a highly self-censored society. Drawing from 10 months of ethnographic observation during China's COVID-19 lockdown in 2022, the study finds that physical spaces, like PCR testing booths, enabled more candid conversations between informal settlers, urban residents, and lower-tier state officials, compared to online platforms under tight surveillance.